Despite its strong economic performance since the 2000s, the French pork industry is characterised by significant inequalities between its various nodes, as well as between male and female farmers. It also comes at a high cost to society, raising questions about its future.

Building on studies on the dairy cattle industry (November 2023) and the beef cattle industry (September 2024), BASIC and the Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme (Foundation for Nature and Mankind) turned their attention to the pork industry, the creation and distribution of value between its various nodes, and the societal costs it generates.

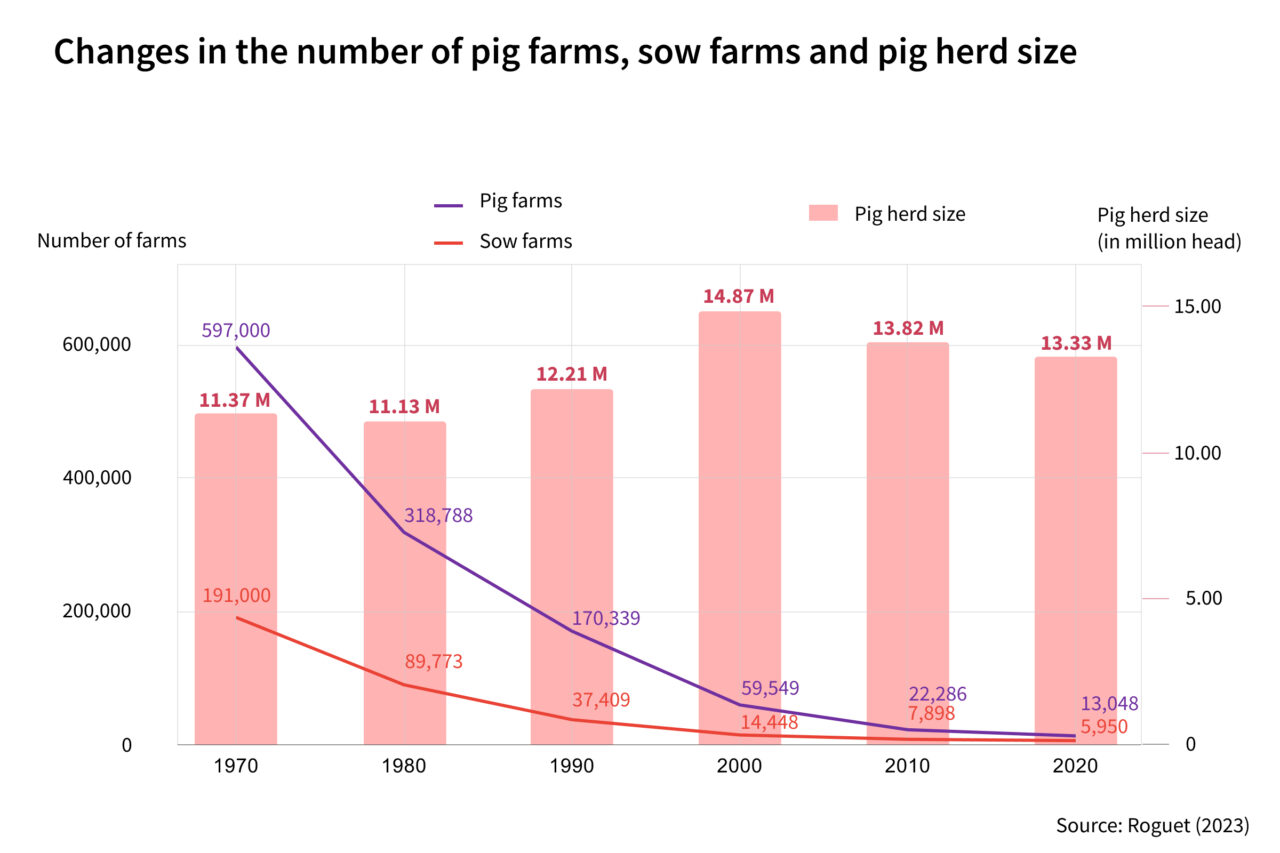

The pork industry has undergone a transformation since the 1960s. Production volumes and rhythm have increased, while the number of players has decreased due to a phenomenon of concentration that has led to the creation of large, even very large structures, with a growing number of farms with more than 2,000 pigs.

Production has been standardised and massified (a phenomena called ‘commoditisation’) in order to respond to fierce competition from European manufacturers such as Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, who are engaged in a race for price competitiveness.

An industry that mainly benefits large retailers

This competition eliminated smaller players and reduced the number of slaughterhouses tenfold between 1968 and 2023. The difficulties faced by the processing sector are encouraging companies to consolidate in order to achieve economies of scale and give them greater bargaining power with respect to supermarkets and hypermarkets.

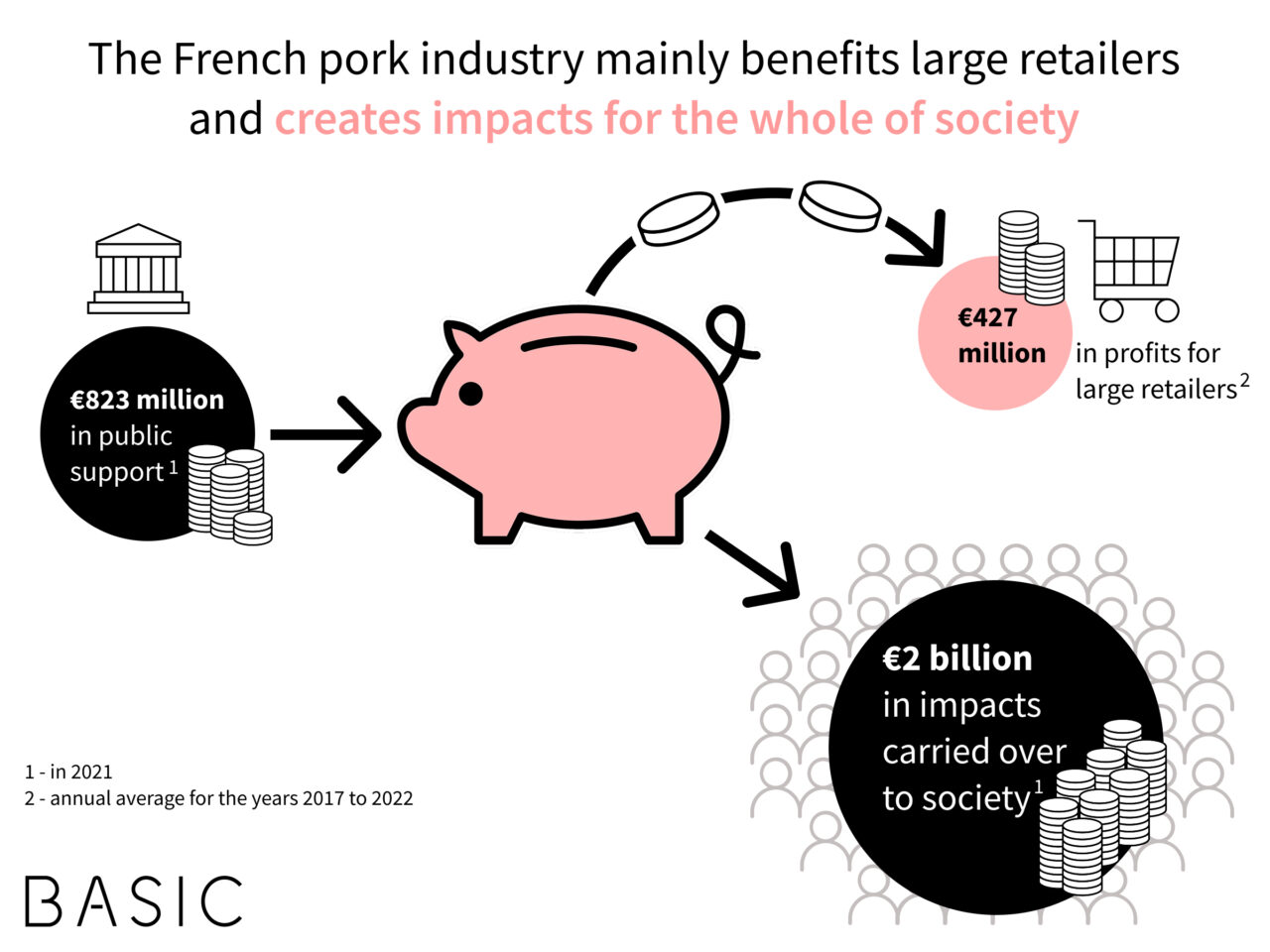

While many manufacturers are suffering, this is not the case for the distribution sector. Large and medium-sized retailers generated an average of €427 million in net profits per year from the sale of pork charcuterie products between 2017 and 2022. This represents one-fifth of the total profits of large retailers, all departments combined (including loss-making departments). Private labels clearly dominate this sector: they account for just over half of charcuterie purchases in supermarkets and hypermarkets, with 91% of charcuterie purchases for home consumption taking place in this type of store.

On average, pig farmers are also doing rather well. Pig farming is one of the most lucrative agricultural activities. However, it is characterised by significant income inequality. While 7% of farms lose money, the richest 10% earn six times the average income of this agricultural profession.

Speaking in June at a gathering of pig farmers, French Agriculture Minister Annie Genevard praised the “central role” they play “in regaining our country’s food sovereignty.” However, France’s trade balance for pork products has been negative in value since the early 2000s. The French industry is locked into a model where it exports low value-added products (live animals, carcasses, offal, etc.) and imports high value-added products (dry charcuterie) or low-cost raw materials to manufacture charcuterie in France. It is thus subject to growing imports from Spain for the industrial manufacture of cooked ham in France as well as imports of highly standardised and inexpensive charcuterie products by large retailers.

High costs for society and a serious reason to initiate a transition in the sector

All these factors paint a more nuanced picture than the one often portrayed of a high-performing industry. But to get a complete picture, we must also consider the costs of the pork industry. We have therefore calculated the public subsidies it receives and the amounts spent to mitigate its impacts.

Public authorities (the State, the European Union, etc.) spent €823 million in 2021 to support the various nodes in the pork industry chain. This mainly took the form of operating subsidies for pig farmers and social security and tax exemptions for all nodes in the chain (production, processing, distribution, catering).

Public expenditure aimed at mitigating the impact of the industry is even higher. It reached at least €2 billion in 2021. This is mainly health expenditure caused by the overconsumption of processed meat. The latter far exceeds health recommendations and thus causes diseases such as diabetes and colorectal cancer. Added to this expenditure is the cost of dealing with the ecological impacts, in particular air pollution from ammonia and water pollution from nitrates.

In light of this observation, several studies have shown that alternative pathways are possible. These include the dissemination of agroecological practices (free-range farming, straw bedding, non-industrial animal feed, reconnecting livestock farming with crop cultivation, etc.), ending the specialisation of certain areas in pig farming, redeploying small farms across the whole territory, and reducing the size of farms. Public health stakeholders are also calling for a reduction in meat consumption and a reconsideration of the use of nitrite additives.

In light of these challenges, public policies must drive the sector’s shift toward food autonomy, rural employment, and resilience, instead of letting the European common market and global trade dynamics shape relationships in the pork industry and worsen their effects.

👉 Read the study (in French) on the website of the Fondation pour la nature et l’homme